Day 30: LA JALOUSIE (JEALOUSY) (Philippe Garrel, France, 2013)

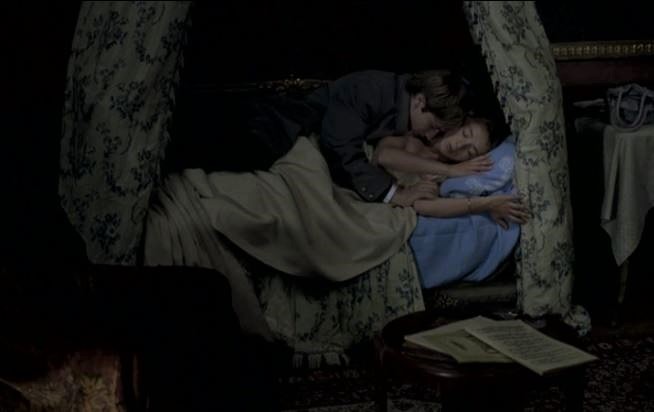

There’s a density to the images of a Philippe Garrel film that I’m increasingly convinced are exceptional to the medium; rarely fussy or even overtly composed, typically it’s just actors talking and interacting in a series of underfurnished interior rooms connected by transitory public spaces like streets and parks. And yet, somehow, each moment seems imbued with a kind of mythic aura I tend to associate more with Greek tragedy than the cinema. La jalousie replays a story of triangulated romantic complications of the type Garrel explores in many of his films, with the autobiographical overtones taking on additional layers of meaning with the casting of his son, Louis, as his stand-in (his daughter, Esther, has a major role as Louis’s character’s brother—so many layers of familial implication braided into this film!).

The magnificent Anna Mouglalis, who I think has definitely confirmed her place as my favorite contemporary French actress (sorry Isabelle and Juliette), is the world-weary actress Louis leaves his wife for in the film’s opening sequence, and just as one assumes they know what kind of “jealously” the title refers to yet another subtle variation surfaces, and by the end it’s clear a whole typography of jealous impulses—romantic, familial, professional, etc—have been delicately excavated and examined. And none of this conveys that immense beauty of the images themselves, the work of Willy Kurant (who lensed for Varda, Godard, Robbe-Grillet, Marker, Gainsbourg and others in the sixties and seventies). The oversaturated black and white suspends 2010’s Paris in a space beyond the trappings of any specific year (it feels like 1963 just as much as 2013). In the most condensed of running times—this one clocks in at a characteristically succinct 77 minutes—Garrel is able to articulate and convey more than most films twice as long.

[Watch La jalousie on Fandor here.]

There’s a wonderful, extended sequence early on involving Colin, where, alone his bedroom, a despondent feeling of restlessness slowly gives way to a spontaneous, ebullient catharsis as he tentatively begins to dance to a record of The Animals’s rollicking “Hey Gyp.” Mumbling along with a few English phrases, epileptically keeping time to the beat, it’s the type of private moment usually experienced alone behind locked doors, which makes it all the more remarkable to witness on a screen (also, one can’t help but feel the enigmatic conclusion to Beau Travail starting to germinate here).

There’s a wonderful, extended sequence early on involving Colin, where, alone his bedroom, a despondent feeling of restlessness slowly gives way to a spontaneous, ebullient catharsis as he tentatively begins to dance to a record of The Animals’s rollicking “Hey Gyp.” Mumbling along with a few English phrases, epileptically keeping time to the beat, it’s the type of private moment usually experienced alone behind locked doors, which makes it all the more remarkable to witness on a screen (also, one can’t help but feel the enigmatic conclusion to Beau Travail starting to germinate here). And while I’m not exactly sure what the exact circumstances are that have has made this film so completely unavailable, it wouldn’t surprise me if the soundtrack, which is chock full of English language music from the period (not just The Animals, but Nico, The Rolling Stones, The Yardbirds, Prince Buster, among others), poses substantial rights issues. Which is unfortunate, because it really is itself an important rite of passage exercise in Denis’s overall filmmaking trajectory; admirable on its own, but even more impressive when considered within the context of her ever-expanding body of work.

And while I’m not exactly sure what the exact circumstances are that have has made this film so completely unavailable, it wouldn’t surprise me if the soundtrack, which is chock full of English language music from the period (not just The Animals, but Nico, The Rolling Stones, The Yardbirds, Prince Buster, among others), poses substantial rights issues. Which is unfortunate, because it really is itself an important rite of passage exercise in Denis’s overall filmmaking trajectory; admirable on its own, but even more impressive when considered within the context of her ever-expanding body of work.

And, on a more personal note, there’s also a layer of poignance and resonance for me when watching de Oliveira’s films of sensing my own family history surfacing on the screen: my family roots also lie in rural Porto of the north, and at unexpected moments—in the walk of an old woman, the swing of a grape hoe, or, most particularly, the traditional songs—I can almost sense, for just a split-second, my family mythologies come to life before my eyes. And for me, that is much more magical than the appearances of the ghostly specter of the title.

And, on a more personal note, there’s also a layer of poignance and resonance for me when watching de Oliveira’s films of sensing my own family history surfacing on the screen: my family roots also lie in rural Porto of the north, and at unexpected moments—in the walk of an old woman, the swing of a grape hoe, or, most particularly, the traditional songs—I can almost sense, for just a split-second, my family mythologies come to life before my eyes. And for me, that is much more magical than the appearances of the ghostly specter of the title.