IMPATIENCE (Charles Dekeukeleire, 1928) [08/29/19, YouTube]

In her pioneering (and as far as I can tell still-definitive) essay on the Belgian director, Kristin Thompson describes this 35 minute experimental film a “remarkable work,” and I’m inclined to agree. I can’t hope to match her meticulous description of its intricate structure and form, which is grueling even by the standards of the non-narrative avant-garde. But I quickly found its rigid, repetitious editing style hypnotic–it brought to mind Cubism, of trying to “get” at something by presenting it from as many angles as possible. There is also, as Thompson notes, an undeniable, underlying eroticism to the film; I’d go even further and posit the pulsating, fetishistic charge is only barely constrained by the strict form. Enigmatic and intriguing.

THE OLD DARK HOUSE (James Whale, 1932) [08/25/19, Kanopy]

Second viewing, and while its odd fusion of horror and camp humor still doesn’t quite gel for me, it sure is a pleasurably frenzied 70 minutes. Whale is such a master at orchestrating slyly suggestive gestures and visual cues (fragmented mirrors, shadowplay, knife wielding, double meanings, fluttering hand gestures, removed shoes, gender ambiguity, etc), and the decrepit mansion of the title is a wonderfully queer space in all senses of the term: non-normative, liminal, unapologetically nonsensical. Seeming to operate by the spatial logic of M.C. Escher, literally anything seems possible from one moment to the next at the Femm Manor, and one by one each member of the family is revealed to be much less, err, straightforward than they initially seem. And seeing the film today, there is the undeniable thrill in seeing Gloria Stuart–so iconic to my generation as old Rose in Titanic–in the full bloom of youth.

THE MOTHER AND THE WHORE (Jean Eustache, 1973) [08/23/19, Pacific Film Archive]

Second viewing. I first saw this exactly fifteen years ago in London, during my undergrad semester abroad. Frankly, the details of the screening–a morning start time, and what felt like three of us in a cavernous screening room–has lingered longer than anything about the film itself, and I’ve been long wanting to revisit as I’ve suspected that having more life experience under my belt would make the film more resonant. It did.

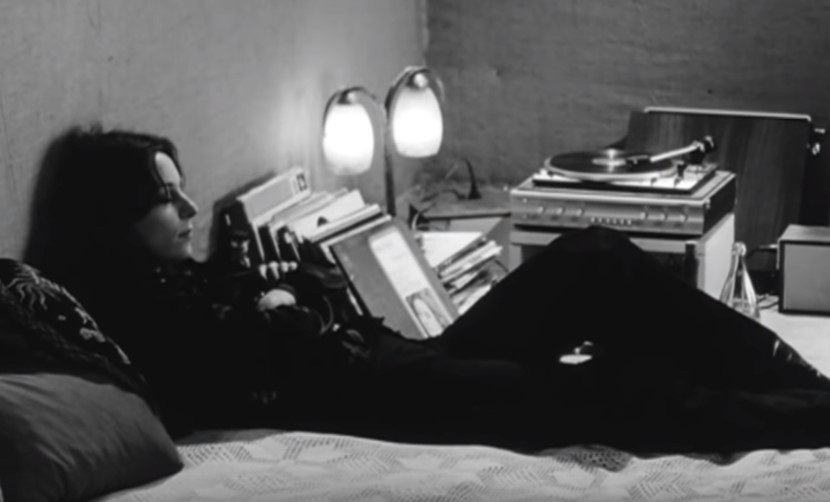

Today I find the general premise slightly queasy (“charmingly” chauvinistic Parisian male romantic hijinks), but this is quickly neutralized and then overpowered by the immensity of the project. The women quickly, mercifully crowd out Léaud. Lebrun is impressive but has the flashier role; what has continued to stick with me is the deserted Lafont putting on a record and lying on the bed, we then proceed to listen to the entirety of Piaf’s whirligig “Les Amants de Paris.” It feels like we watch her live a whole lifetime in just those several minutes. I’ve lived those types of minutes too.

THE HOUSE WITH NO STEPS (William Ungerer, 1979) [08/20/19, Kanopy]

Watched on a complete whim and with no foreknowledge of what it was (a rare experience for me), and though distributed through Canyon Cinema it’s less experimental than an independently produced drama made in an observational mode. As we’re introduced to a number of townspeople in rural Vermont it’s interesting for a while in the way something like Winesburg, Ohio is interesting, and it does indeed capture the type of social claustrophobia particular to small town life in rural America. But in the end all the interesting characters and plot points never seem to quite coalesce into anything beyond their individual elements.

THE QUEEN (Frank Simon, 1968) [08/19/19, DCP, Castro Theatre]

Second viewing. For such a towering monument of queer cinema, it’s a rather slight film–thought admittedly that’s a major source of its poignance and charm. Beautifully restored and becoming widely available at long last, the time for its ascension finally seems upon us.

THE VELVET VAMPIRE (Stephanie Rothman, 1971) [08/13/19, Amazon Prime]

An elegant art film masquerading as a salacious softcore skinflick; Daughters of Darkness (a great favorite of mine) is the most obvious comparison. Rothman cleverly frames the limitations of her actors as a kind of dreamy, Antonioni-esque ennui, everything seems trapped in a suspended state. The surname of Yarnall’s character, LeFanu, clearly connects the film to Sheridan LeFanu’s female-centric, diurnal vampire classic Carmilla, and similarly undermines genre expectations at every turn. Never given a chance to graduate from Roger Corman productions into mainstream productions–a tragedy–Rothman was later told by a studio that they had hired a neophyte director to make a vampire film “sort of like Velvet Vampire,” which turned out to be The Hunger by Tony Scott. The lineage is obvious.

MURIEL’S WEDDING (P.J. Hogan, 1994) [08/10/19, Home viewing screening]

A perfect example of a how a film doesn’t have to deal with anything obviously “queer” to be a queer film classic. The intense queer resonances are instead social, emotional, and the sense of being marked as different–and demanding happiness despite it. The breakneck character arcs, dialogue exchanges, and plot rhythms are the stuff of 1930’s screwball comedy, and as she gamely endures the endless little humiliations on her way to triumph, Toni Collette earns a place alongside the genre’s most iconic heroines.

SUNSET BLVD. (Billy Wilder, 1950) [08/10/19, Stanford Theatre)

Multiple viewings. Endlessly rewatchable, and indisputably one of Hollywood’s great achievements; I can never manage to muster up much affection for it, however, and have never regarded it as a favorite. For all its individual moments of humor–and the camp pleasure of Norma’s histrionics–it takes conscious effort to avoid getting swallowed up by its sadness, and it’s impossible not to walk away feeling more than a bit dirtied by the contact. With each subsequent viewing it sure is beginning to seem like von Stroheim is the actual center of the film, giving the tragedy moral weight.

MUR 19 (Mark Rappaport, 1966) [08/06/19, Kanopy]

The type of first film that seems to lay out all of a director’s specific cinematic preoccupations and concerns yet to come.

MOONSTRUCK (Norman Jewison, 1987) [08/03/19, Amazon Prime]

Made me realize how much I miss this type of unpretentious, cheerfully professional Hollywood filmmaking. For a while everything is good-natured ethnic cliché and slightly musty screwball comedy plot mechanisms, but quickly real people and emotions emerge out of the narrative contrivances. The sense of melancholy Cher gives brash Brooklynite Loretta Castorini is deeply touching, and she and Nicolas Cage–truly a most unexpected romantic pairing–are simply electric together.