This post is a contribution to the Queer Film Blogathon, hosted by Garbo Laughs.

During the last few months I have had the opportunity to see two films rather striking in their many similarities. Both Mädchen in Uniform (Leontine Sagan, Germany, 1931) and Olivia (The Pit of Loneliness) (Jacqueline Audry, France, 1951) are films set in the all-female world of exclusive boarding schools and feature emotionally charged teacher/student pairings with unmistakable erotic dimensions. Also notable is that both are directed by female directors, a rarity in both Germany and France at the time. And, unfortunately, they have also suffered similar fates: both have been difficult to find on home viewing formats in the United States, as those who have held the American rights to both films have resisted the lesbian element of the films and for many years refused to allow them to be shown in the context of female and/or queer film festivals. Aside from making what are interesting and important films difficult to see, the historical repression of both of these films have the lamentable effect of making the cinematic representation of lesbianism and lesbian desire in the past appear even more marginal than it already does.

Of the two films, Mädchen is the more recognizable, remaining a generally well-known film despite being relatively little-seen—no history of queer film is complete without establishing the influence of Sagan’s ground-breaking film. Helping matters is that it is a cinematic masterpiece and has generally been considered from the very beginning (the film is included, for example, in Lotte Eisner’s seminal The Haunted Screen: Expressionism in the German Cinema). As such, I will primarily focus the rest of this post on Audry’s Olivia, and use Mädchen as a more well-known point of reference and comparison (for those interested in reading more on the film, I recommend two other posts on the film that have been included in this Blogathon—see them here and here).

I got the opportunity to see Olivia, released in America under the inexplicable title The Pit of Loneliness recently as part of a series hosted by San Francisco’s Frameline Film Festival, the longest running and largest LGBT film festival in the world (it concluded its 35th festival yesterday). Sponsored by the library system, it featured free screenings of several films from the organization’s archives. It was, unfortunately, a less-than-ideal circumstance: though Frameline owns a supposedly gorgeous 35mm print of the film that was acquired when it was given a retrospective screening at the festival a number of years ago, what we saw was a DVD dupe made from a VHS dupe of the film, and it did the sumptuous black and white cinematography no favors. And between the sparse white-on-white subtitles, less-than-ideal audio quality and my elementary grasp on conversational French I’m sure that I missed a number of nuances and subtleties (especially as it’s one of those French chamber pieces where everyone talks and talks and talks…).

That said, a rare screening of a rare film is always something to treasure, and I’ll just hope I get to see the film again someday under more ideal circumstances. Because what I did see and was able to catch was fascinating, not only in its similarities to Mädchen, which it very much resembles in a very general sense, but in the many differences between the two films. In some ways the two films could be considered the flipside of the same coin, each serving as a counterpoint of sorts for the other. It is this dynamic I’d like to tease out in the rest of this post.

As previously mentioned, director Jacqueline Audry is probably the most well-known of the several female directors who made films in France after the heady avant-garde years of the 1920’s and Agnès Varda appeared on the film scene in the late 50’s. She is most remembered for the three Colette adaptations she directed in the 1940’s and 50’s, particularly the non-musical first version of Gigi (1949). Though it is commonly assumed that Olivia is also Colette adaptation, as pointed out by queer film historian and Frameline’s curator Jenni Olson, the film is actually an adaptation of a novel by Audry’s sister Colette Audry, a well-known writer in her own right, and the enterprising American distributor simply lopped off the author’s last name to try and capitalize on the director’s previous association with the eminent French Modernist writer (ingenious from a marketing standpoint, but confusing!). The story, which is believed to have some autobiographical resonances, revolves around the titular character arriving at a French all-girls finishing school run by two elegant headmistresses, Mlle. Julie (played by celebrated French stage actress Edwige Feuillère) and Mlle. Clara (Simone Simon, famous for films made on both sides of the Atlantic, particularly Cat People). As Olivia is almost immediately informed by one of her classmates, the student body is divided into two camps: those devoted to Mlle. Julie and those to Mlle. Clara.

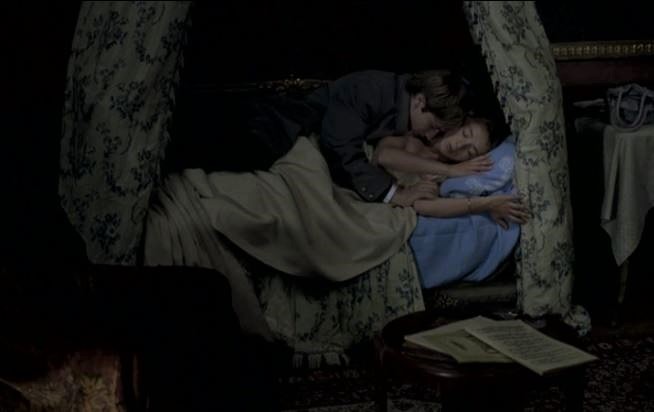

Olivia at first becomes enamored with the former after aiding in a number of nighttime rituals including combing her hair, fanning her tenderly, etc (“keep making a fuss of me, I love it!” she purrs to the clearly adoring young girls).

The seductive if playful undertone to Mlle. Clara’s voice is the first indication of what exactly the affection of the student body might entail. But after being moved by one of the nightly recitations of a Racine play, Olivia catches her instructor’s eye and she quickly establishes herself as Mlle. Julie’s favorite pupil. The admiration quickly begins to take on a more amorous dimension, which becomes obvious after Laura, Julie’s past favorite, reappears at the school. Despite befriending Laura, Olivia can’t help but feel competitive for their teacher’s attention, and Olivia even attempts to ask Laura to help her define her feelings for Mlle. Julie. “Do you love her?” she asks Laura, who doesn’t seem to catch the true nature of the question, and responds that she owes everything to the headmistress. Olivia tries again: “doesn’t your heart beat when she’s with you, or stand still when she touches your hand?” Laura, seeming now to comprehend, definitively says no, stating “I just love her. There is nothing else,” and promptly leaves the room.

The plot thickens as it becomes clear that beneath the antagonism of the two headmistresses is a once-intimate relationship of an unspecified nature between the two that at some point soured. It all comes to a head during the annual Christmas party—complete with Mädchen-style male drag by the students—that Mlle. Julie promises to stop by her room later that night(!). At this point it is made explicit that this is not merely some one-sided schoolgirl infatuation of Olivia’s but that there are some kind of mutual feelings involved, which is emphasized by Mlle. Julie’s unexpected decision to leave the school, as it is the “best thing to do.”

This underscores one of the major differences between Olivia and Mädchen: though there are many parallels to draw between the relationship that springs up between student and teacher, there’s a very profound difference in the fact that it is not just one of the teachers, but the headmistress—that is, the person in charge—that is experiencing these feelings. Instead of the antagonistic dynamic of Mädchen which creates a “they just don’t understand the nature of our love!,” us-versus-them storyline, Olivia becomes more about the walls of the boarding school potentially functioning as a haven-like space for lesbian feelings and desires apart from the world, something Mlle. Julie sternly warns Olivia of in the climatic sequence. Mlle. Julie seems aware that there might be potential for sustaining a lesbian relationships in this cloistered, isolated setting—as it might have indeed done for Mlles. Julie and Clara at one point—but the reality is that the world outside brutally refuses such things (“and what if you are defeated, Olivia?” Mlle. Julie evocatively but elusively muses at the end of the film, not specifying as to what exactly she is speaking of).

The entire mise-en-scène of the film seems to underline this crucial different between Olivia and Mädchen—where the boarding school of the latter is composed of harsh, hard angles to visually emphasize the militaristic, almost tyrannical nature of the school, the boarding school of the former is soft, embracing and marked by graceful curves echoed by the languid camera pans. This is seen most prominently in the staircases that feature prominently in both films: where Mädchen‘s central staircase is composed of sharp right angles and tightly tiered like the nightmarish staircase straight out of Vertigo, the central staircase in Olivia serves not only as a central meeting place for the school, but the showcase for its elegant headmistress, who is introduced in the film as ascending from upstairs into a twittering nest of fawning students.

Clearly, both Olivia and Mädchen in Uniform are incredibly important films that deserve to be more widely released and seen, and taken together, function as two complimentary but in many ways different takes on the possibility of love and desire between women in pre-Stonewall cinema.

This post is in contribution to the Queer Film Blogathon, June 2011.

One of my favorite things is to sit and gab with two of my “uncles”–a gay couple now in their late 80’s and early 90’s respectively–and listen to their memories of films and stars from the Hollywood studio era, and, most especially, all the juicy gossip that circulated in gay circles (who cares if it was ever true or not?). It always fascinates me how vibrant many of these stories and perceptions remain for them, and what shape that they take. For me, these conversations serve as a vivid demonstration of what queer scholars have been writing about for decades–what Dyer describes in the groundbreaking collection of essays he edited Gays and Film as a kind of “queer bricolage.” Taking the term directly from French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, he defines “bricolage” as “playing around with the elements available to us in such a way as to bend their meanings to our own purposes.” Through this process “we could pilfer from straight society’s images on the screen such that would help us build up a subculture, or what Jack Babuscio calls a ‘gay sensibility.'”

One of my favorite things is to sit and gab with two of my “uncles”–a gay couple now in their late 80’s and early 90’s respectively–and listen to their memories of films and stars from the Hollywood studio era, and, most especially, all the juicy gossip that circulated in gay circles (who cares if it was ever true or not?). It always fascinates me how vibrant many of these stories and perceptions remain for them, and what shape that they take. For me, these conversations serve as a vivid demonstration of what queer scholars have been writing about for decades–what Dyer describes in the groundbreaking collection of essays he edited Gays and Film as a kind of “queer bricolage.” Taking the term directly from French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, he defines “bricolage” as “playing around with the elements available to us in such a way as to bend their meanings to our own purposes.” Through this process “we could pilfer from straight society’s images on the screen such that would help us build up a subculture, or what Jack Babuscio calls a ‘gay sensibility.'” embedded in the films of the past, often wittily recasting these films in our own image. Christianne over at

embedded in the films of the past, often wittily recasting these films in our own image. Christianne over at  Russell co-stars with Robert Mitchum, and this is the first of two films in which she was paired with Mitchum, with the second, Joseph von Sternberg’s Macao from the following year the one most usually remembered (despite being overall the lesser film). I had never heard of His Kind of Woman before when I checked out the DVD from my local library on a whim, and was immediately charmed by it–Russell and Mitchum make one of my very favorite screen pairings (now there’s a man that’s Russell’s equal!), their banter is bright and witty, the mood and black and white photography is appropriately atmospheric, and there’s the’s one amazing, bravura tracking shot through a vintage 1950’s resort lounge that ranks with the best of Ophüls. People often cite Vincent Price’s comic relief as one of the film’s chief attributes as well, but I can’t say I’m not particularly fond of it myself.

Russell co-stars with Robert Mitchum, and this is the first of two films in which she was paired with Mitchum, with the second, Joseph von Sternberg’s Macao from the following year the one most usually remembered (despite being overall the lesser film). I had never heard of His Kind of Woman before when I checked out the DVD from my local library on a whim, and was immediately charmed by it–Russell and Mitchum make one of my very favorite screen pairings (now there’s a man that’s Russell’s equal!), their banter is bright and witty, the mood and black and white photography is appropriately atmospheric, and there’s the’s one amazing, bravura tracking shot through a vintage 1950’s resort lounge that ranks with the best of Ophüls. People often cite Vincent Price’s comic relief as one of the film’s chief attributes as well, but I can’t say I’m not particularly fond of it myself.

and The Silver Screen: Color Me Lavender (USA, 1997). Indeed, both films serve as wickedly clever and irreverent re-readings of orthodox–and resolutely heteronormative–film histories. The aim of these two films is to reveal the queer resonances subtly (or often not-so-subtly) embedded within classic cinema. In the wake of Rock Hudson’s very public coming out and death from AIDs in 1985, Rappaport scans back through the actor’s extensive filmography, and begins to reveal that far from being some unknown secret, Hudson’s closeted sexuality seems to manifest itself in countless ways throughout his decades-spanning filmography. “It’s not like it wasn’t up there on the screen,” narrator Eric Farr intones in the introduction of the film, “if you watched the films carefully.” The was vividly re-confirmed for me at a screening of Sirk’s glorious Written on the Wind at the

and The Silver Screen: Color Me Lavender (USA, 1997). Indeed, both films serve as wickedly clever and irreverent re-readings of orthodox–and resolutely heteronormative–film histories. The aim of these two films is to reveal the queer resonances subtly (or often not-so-subtly) embedded within classic cinema. In the wake of Rock Hudson’s very public coming out and death from AIDs in 1985, Rappaport scans back through the actor’s extensive filmography, and begins to reveal that far from being some unknown secret, Hudson’s closeted sexuality seems to manifest itself in countless ways throughout his decades-spanning filmography. “It’s not like it wasn’t up there on the screen,” narrator Eric Farr intones in the introduction of the film, “if you watched the films carefully.” The was vividly re-confirmed for me at a screening of Sirk’s glorious Written on the Wind at the  –and rumored lovers–Cary Grant and Randolph Scott to comedians like Bob Hope, Jerry Lewis, and Danny Kaye, and on to supporting characters such as Walter Brennan and the “sissies” of 1930’s Hollywood cinema such as Eric Blore and Edward Everett Horton. Of course there’s quite a bit of taking clips and quips out of context, and much of the effect comes from the narrator’s coy lead-ons that color the viewer’s perception, but that’s a great part of the charm and campy fun of it all. But it’s Rappaport’s consistent daring to go there is what makes his films so illuminating and, sometimes, truly profound.

–and rumored lovers–Cary Grant and Randolph Scott to comedians like Bob Hope, Jerry Lewis, and Danny Kaye, and on to supporting characters such as Walter Brennan and the “sissies” of 1930’s Hollywood cinema such as Eric Blore and Edward Everett Horton. Of course there’s quite a bit of taking clips and quips out of context, and much of the effect comes from the narrator’s coy lead-ons that color the viewer’s perception, but that’s a great part of the charm and campy fun of it all. But it’s Rappaport’s consistent daring to go there is what makes his films so illuminating and, sometimes, truly profound.