Remarkable, but I’m not sure if I have anything particularly coherent to say after a first viewing: like a dream, it moves through its series of gorgeously evocative sequences and images that accumulate and deliquesce, ebb and flow–a beautiful way to convey communication difficulties, one of the topics the film is clearly grappling with. While not as explicitly (homo)sexual as Anger’s Fireworks, one still senses how the frisson of sexual difference gives the images an extra charge, which all culminate in a private and highly symbolic encounter that might be a religious experience or maybe a sexual rendezvous–or perhaps both? Michael Koresky’s entry on the film in his essential Queer and Now series, is, well, essential reading, and makes me excited to return to it again ASAP.

A CANTERBURY TALE (Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger, 1944) [11/29/19, Criterion Channel]

Second viewing. I’ve been meaning to revisit for years and years–not only did I have a very compromised first experience (a barely watchable VHS dupe, as I recall), but had literally forgotten all details about its plot. And yet traces of it clearly stuck with me, and over the years shivers of memories of its final scene would surface whenever I found myself in grand spaces intended to inspire and awe, and cathedrals in particular. Upon this return I admit it doesn’t exactly work for me, but recognize the qualities that provoke such strong reactions in others–this is very much the type of film that can cast a spell of enchantment, superseding what is actually going on on the screen and alighting upon something almost ineffable. In their film debuts Sheila Sim (a theater actress) and John Sweet (a non-professional American soldier) are both absolutely wonderful, bringing an unaffected quality to their performances as outsiders finding themselves stranded in a tiny rural English town due to the war, and instead of plot Powell and Pressburger focus on the type of evocative details that vividly capture an entire way of life in the process of disappearing forever. Lightly impressed upon this tale of the everyday is Chaucer’s immortal Canterbury Tales, allowing for the delicate interplay of history with the imperiled present–Peter von Bagh describes it as “mythical neorealism,” which is just perfect)–which all finally crescendos in the famous climactic sequence in nearby Canterbury Cathedral. Okay, as I’ve been writing about it now I feel like I’m convincing myself I actually liked it much more than I initially thought I did. Perhaps it’s the type of film that comes most alive while in the memory…

THE ILLUSTRATED AUSCHWITZ (Jackie Farkas, 1992) [11/27/19, Vimeo]

The concept–playing the oral testimony of Auschwitz survivor Zsuzsi Weinstock over a series of brightly colored, random-seeming images shot on flickering Super 8 film–at first seems much to flimsy to support a discussion of such emotional and historical enormity as the Holocaust. But the lack of imagery that has now become so closely associated with the Holocaust (deportation trains, camps, emaciated bodies) quickly has the effect of jolting the viewer out of preconceived notions of how to process the information we are experiencing, allowing us receive the full shock of the testimony. Then, in an utterly unexpected move, the quivering images begin focusing on something familiar: the face of young Judy Garland in The Wizard of Oz, a film also deeply aware of complexities of longing for a lost home and an unrecoupable past self. The familiar, iconic images of Oz are made strange through Farkas’s manipulation of the image, and Weinstock’s words immediately begin to draw upon the intense emotional inflections of the beloved film and its musical score, and suddenly the film bursts in uncontrollable emotional affect. A tremendous achievement, and all in under thirteen minutes. I can’t believe I’ve only just heard of it (via Deb Verhoeven’s ballot for BBC’s [meh] poll of the 100 Greatest Films Directed by Women).

Farkas has generously made the film available on her Vimeo account.

ATLANTICS (Mati Diop, 2019) [11/26/19, Movie Theater]

I knew only of the buzz coming out of Cannes (where it won the Grand Prix) + my admiration of Diop’s stoic performance in Claire Denis’ 35 Shots of Rum and I’m glad I didn’t know anything more, because this just completely knocked me out. Just several minutes in I fell under its hypnotic spell almost immediately, a bravura long shot establishing a palpable sense of tension and feeling of despair that permeates everything that follows. Centered around Ada, a young woman torn between the wealthy man she is engaged to and the working class man she is attracted to,the film quietly follows as she copes with the news that the latter left one night without a word, deciding to try his chances at stealing away to Spain by boat and try to build a better life for himself. Ada’s world is turned upside down and the film itself is similarly upended, beginning to turn inside out and then transforming into a whole new film. I hesitate to say much more, but the effect startled me and then left me exhilarated. No new release I’ve seen this year has come close to touching what Diop miraculously pulls of here; more than just an excellent film, I left the theater with a renewed excitement for the possibilities of contemporary cinema.

BATHTUBS OVER BROADWAY (Dava Whisenant, 2018) [11/18/19, Netflix]

I love watching documentaries solely focused on a person’s esoteric interests and hobbies. Such docs are rarely more than functional in regard to form–and that is the case here–but it is riveting to watch one man (longtime Late Show with David Letterman writer Steve Young) expound on his indefatigable passion for, of all things, obscure industrial musicals, the mostly forgotten genre of original entertainment revues specifically made for the employees and stakeholders of corporations from the 50’s into the early 80’s. A nice introduction to a fascinatingly niche historical phenomenon.

JUDEX (Georges Franju, 1963) [11/05/19, Criterion Channel]

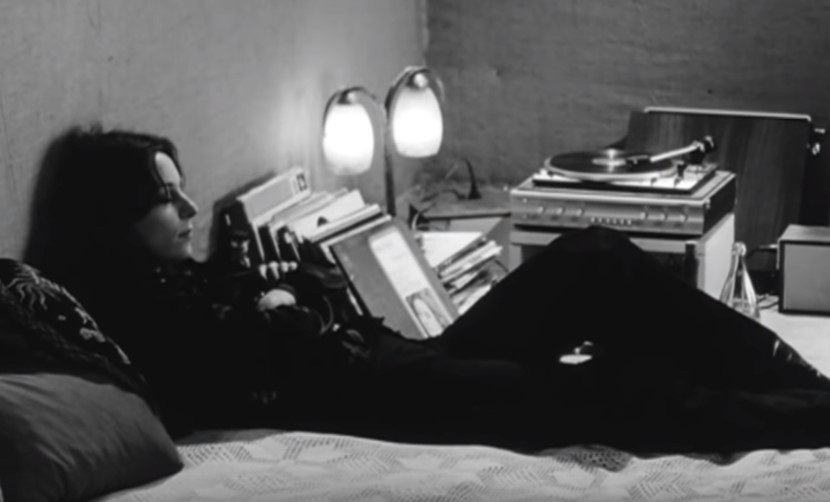

Second viewing. And with just two viewings, Franju’s magisterial distillation of the Feuillade classic (which unfortunately I still have not seen) has established itself as one of my all-time favorite films. Teaming with Feuillade’s own grandson, screenwriter Jacques Chapreux, Franju pares down the original five hour serial to a series of vivid set pieces tenuously strung together by the most delicate dream logic; the elisions in narrative actually allows for a extravagantly languorous and unhurried wander through what Raymond Durgnat perceptively describes as a world “tenderly aware of its own unreality.” The director is clearly more invested in the seductive glamour of villainy than the meting out of moral justice, for even as stoic and handsome Channing Pollack traipses his way through the film with physical grace, he is often (and sometimes literally) sidelined by Francine Bergé, who dons the respectable uniforms of governess and nun before stripping down to an Irma Vep-esque black catsuit to lithely slink across rooftops and through windows. It takes two other female characters clothed in white—ethereal Edith Scob in gauzy flounces and Sylva Koscina in a tight acrobat’s leotard—to counterbalance the heady pleasure of witnessing Bergé’s insatiable and erotically-charged appetite for treachery.

That said, what elevates this film from “mere” clever pastiche or affectionate homage to something legitimately great on its own terms is the exquisite integration of actors into the overall mise-en-scène. The manner in which bodies are choreographed within the frame or almost surrealistically posed and arranged create some of the most unforgettable images to be found in all of cinema: the incredible bird masks at the engagement ball, black-clad bodies improbably scaling walls, guard dogs noiselessly rescuing their imperiled mistress, a fabulously over-the-top nun’s contrasted against the blank expanses of the French countryside, the eerie reflections of a surveillance mirror, a rooftop wrestling match, etc. The luminous black and white cinematography, compliments of Marcel Fradetal, conjures up a heightened, slightly uncanny state that feels like a waking dream. And what is cinema, after all, than some kind of waking dream?

NOVICIAT

NOVICIAT THE ADVENTURES OF PRISCILLA, QUEEN OF THE DESERT (Stephan Elliott, 1994) [09/20/19, Amazon Prime]

THE ADVENTURES OF PRISCILLA, QUEEN OF THE DESERT (Stephan Elliott, 1994) [09/20/19, Amazon Prime] THE MAFU CAGE

THE MAFU CAGE