There’s a reason why the San Francisco Silent Film Festival is considered one of the premiere film festivals in the city (and the world, for that matter), what with its procurement of luminous 35mm prints from international archives, presentations of commissioned restorations, live musical accompaniment, handsomely produced festival booklets, etc, etc. But with individual ticket prices ranging from $15-$20 each, it is, sadly, no friend to a student budget, and I was only able to afford two tickets this year, alas.

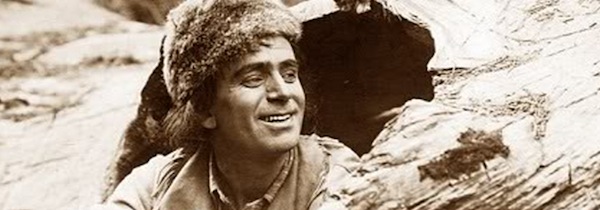

It was with the awareness that Allan Dwan is currently undergoing something of a critical renaissance (a large retrospective in NYC, a massive new 400-page biography by Frederic Lombardi, the release of an equally substantial free(!) e-book of collected essays and reviews, etc) that we bought tickets for The Half-Breed (1916), an early Douglas Fairbanks vehicle that is also one of the prolific director’s earliest feature films. Fairbanks plays the titular character, a man named Lo whose mixed heritage–his Native American mother was cruelly abandoned by his unknown father white–is not fully embraced by either community and so instead makes the wilderness his home. His personal charisma, athletic prowess, and intimate knowledge of nature, however, make him a magnet for the women of a small wilderness town, and the town’s “respectable” men employ racist social conventions as a cover of their utter loathing of his existence and justify their violent plans to excise him from

Expensively made and ambitious in scope, it was a box office flop, and according to the introductory lecture at the screening, Fairbanks in particular tracked all incoming receipts, and from that point forward always made sure to carefully cater his performances to public expectations.  Because this is not at all the Doug Fairbanks of the wide grin and broad gestures, but a characterization marked by cross-armed stoicism (Lombardi says its the actor “at his most dour,” which I think is a rather unfortunate and unfair choice of words). Either way, audiences in 1916 weren’t interested in this Fairbanks persona, but it makes for a very naturalistic and extremely dignified performance when viewed today, and all the more interesting because the impassiveness prevents the characterization from ever descending into gross stereotypes. Endlessly utilized by the film as a means through which to point out racial bigotry, religious hypocrisy, and individual and social prejudices of all kinds, Fairbank’s good humor and indignation toward a variety of injustices prevents this from being a one-dimensional portrait of the familiar “noble savage” figure, and instead creates a multi-faceted portrait of a misunderstood man.

Because this is not at all the Doug Fairbanks of the wide grin and broad gestures, but a characterization marked by cross-armed stoicism (Lombardi says its the actor “at his most dour,” which I think is a rather unfortunate and unfair choice of words). Either way, audiences in 1916 weren’t interested in this Fairbanks persona, but it makes for a very naturalistic and extremely dignified performance when viewed today, and all the more interesting because the impassiveness prevents the characterization from ever descending into gross stereotypes. Endlessly utilized by the film as a means through which to point out racial bigotry, religious hypocrisy, and individual and social prejudices of all kinds, Fairbank’s good humor and indignation toward a variety of injustices prevents this from being a one-dimensional portrait of the familiar “noble savage” figure, and instead creates a multi-faceted portrait of a misunderstood man.

But even more than Fairbanks, The Half-Breed features two excellent female performances, by Jewel Carmen and, particularly, the tragic Alma Rubens, both who shine in contrasting roles that are atypically well-rounded for the era–perhaps the result of Anita Loos’s contribution as co-writer of the screenplay. Also worthy of note is Victor Fleming’s work as cinematographer, with the location shooting taking full advantage of the soaring vistas of the Sequoia National Forest. Despite all of these laudable elements, the financial failure of the film upon its initial led to it being frantically recut, and a number of shorter, re-edited versions ended up circulating for years; a reconstruction has been made drawing from all surviving material, and the restoration work on the image is uniformly gorgeous. It’s not exactly a find that’s going to rewrite cinema history or anything, but I hope it is made widely available, because it’s definitely an interesting film well worth seeing (35mm).

_____________

Another powerful–but extremely different–rendering of complex human emotions and interactions playing against the vast backdrop of nature is Victor Sjöström’s The Outlaw and His Wife (1918). The plot is basic: a man who was compelled by circumstances to commit a criminal act is forced into a life of hiding in the bleak expanses of rural Iceland. Eventually he takes on a manual labor position at a farm of a rich and generous widow, and judging from the title alone, it’s not hard to figure out the trajectory of their relationship. Things get more interesting when the man’s past inevitably comes back to haunt him, forcing him to return to hiding, only this time around with his new wife in tow. Sjöström plays the role of the outlaw himself, and it is rather startling to see the man who is most familiar to American audiences as the frail elderly gentleman of Bergman’s Wild Strawberries here appear as a robust (and extremely handsome) young man who gets a job because he can effortlessly sling a large wooden chest over his shoulder and carry it up a ladder. It is also worth noting that the actress who plays the wife, Edith Erastoff, would in several years become Sjöström’s own.

But if I’ve focused almost solely on the acting and storyline, the most impressive and memorable element of the film is the landscape itself, which constantly dwarfs the human figures both in its scale and its unrelenting harshness,  and the interplay between humans and the natural world creates its own sub-narrative to the overall plot. Also crucial to the experience was the musical accompaniment by the Matti Bye Ensemble of the original score composed for the film, and I particularly liked how it emphasized the ethereal qualities of Sjöström’s image’s, and stretches of the film subsequently began to play like a dream. The opening presenter went out of his way to note that it’s a superior score to the one included on the widely available Kino DVD, and I absolutely believe it. Overall I never found the film to quite reach the heights Sjöström achieved several years later with The Phantom Carriage (1921), but it’s an excellent film nonetheless (35mm).

and the interplay between humans and the natural world creates its own sub-narrative to the overall plot. Also crucial to the experience was the musical accompaniment by the Matti Bye Ensemble of the original score composed for the film, and I particularly liked how it emphasized the ethereal qualities of Sjöström’s image’s, and stretches of the film subsequently began to play like a dream. The opening presenter went out of his way to note that it’s a superior score to the one included on the widely available Kino DVD, and I absolutely believe it. Overall I never found the film to quite reach the heights Sjöström achieved several years later with The Phantom Carriage (1921), but it’s an excellent film nonetheless (35mm).